As early as the 1600s in the U.S., our forefathers demonstrated a generous spirit and cared for those who found themselves economically depressed. I don’t mean to sound insensitive to the plight of our ancestors, but I view poorhouse records as the equivalent to land deeds and estate records. In many ways, they are the exact opposite of one another, but both can provide places of residence, family relationships, and vital statistics.

As with Part 1 of this series, I provide examples from my own research to illustrate how I used them to provide a richer description of my ancestors’ lives.

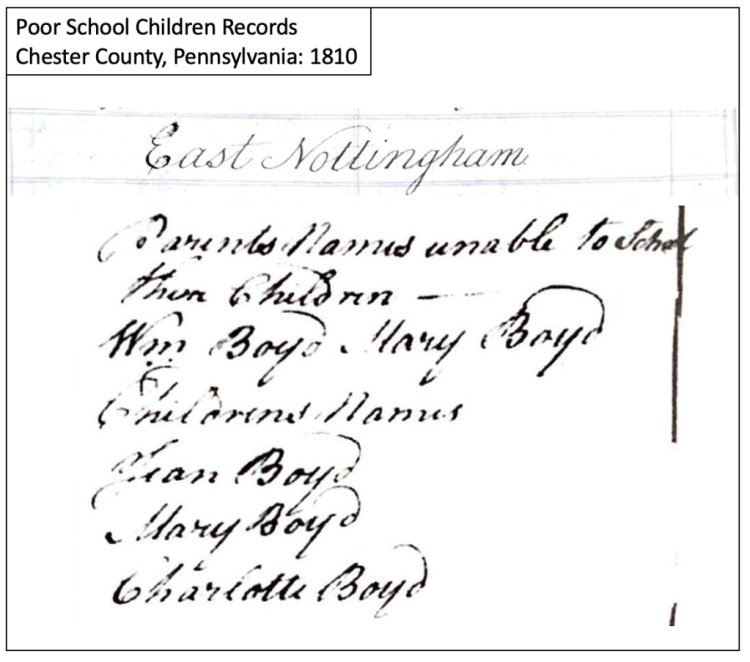

Poor School Children Records

Not all counties and states provide for such early records, but Pennsylvania provided for some of the best I’ve seen. The records I have worked with in Pennsylvania typically cover periods from 1810 through 1842. Usually by community, records list the names of children aged five to 12, whose parents were too poor to pay for their children’s education and thus required county support.[1] Frequently, the children’s father’s name was listed alongside their children’s names.

William Boyd (1753-1836)

As described in the previous blog post, William Boyd’s Revolutionary War pension application indicated he lived for a time near New London Crossroads in Chester County, Pennsylvania.[2] I find him in the 1800 and 1810 census in East Nottingham Township, which is adjacent to New London Township where New London Crossroads is located.[3] In 1810, I also find a Poor School Children record for him, his wife Mary, and three of his children: Jean [Jane], Mary, and Charlotte.[4]

In an earlier blog post, I presented how I connected autosomal DNA matches for Boyds living in Washington and Chester Counties, Pennsylvania to William Boyd using his Revolutionary War pension file. The Poor School Children records also helped me to confirm that the observed autosomal DNA were in fact connected to William Boyd.

In his will, William Boyd left his pension to his daughter, Jane (Boyd) McDonald (1798-1843) of East Nottingham, Chester County thereby completing the link between the poor school child Jane, the autosomal DNA matches to the Boyd/McDonald family of Chester County, and the willed pension.[5] The identity of Mary in the Poor School Children records was later confirmed as Mary (Boyd) Butler (1801-1874) of Washington County. In the obituary for Mary’s husband, Ira Butler, it stated that his wife Mary was born in New London Crossroads in Chester County, Pennsylvania,[6] similarly linking the poor school records, observed autosomal DNA matches to the Boyd/Butler family of Washington County, and the obituary all together. Unfortunately, I have yet to find Charlotte Boyd (b. 1805) in other records.

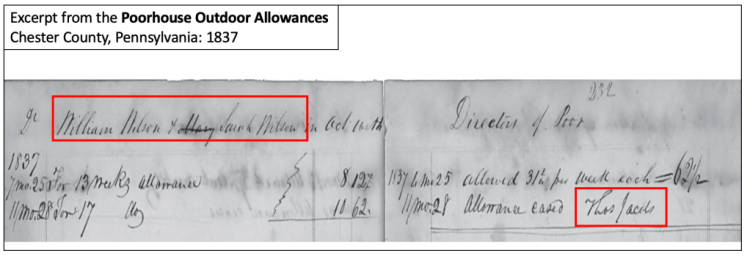

Poor Outdoor Allowance Records

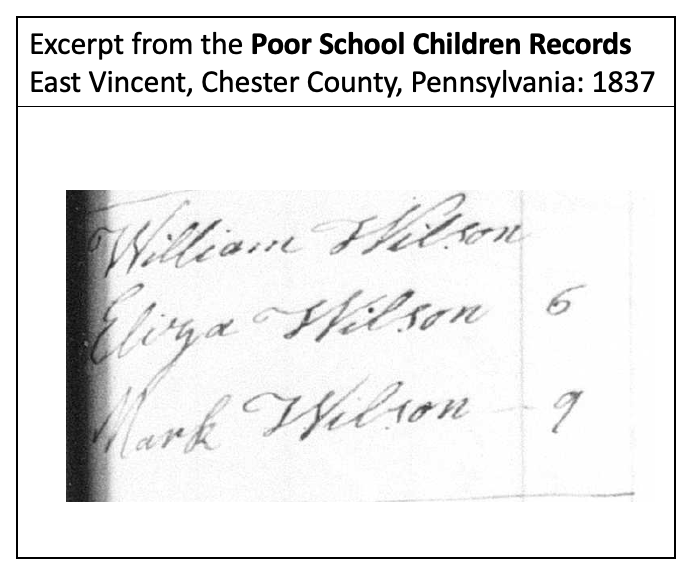

Another type of poorhouse records are the poor outdoor allowances, which are paid out to individuals who were not qualified to be supported in the poorhouse, but who required assistance to live outside of it.[7] In conjunction with poor school children records, I used the poor outdoor allowance records to follow the migration of a 4x great-granduncle, William Wilson (1793-1846), whose reconstructed family was featured in the previous blog post and a copy of the research report is found on my website.

William Wilson (1793-1846)

In 1830, I find William Wilson in Richland, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, which is where his maternal family originated.[8] In 1836, I find a Mark Wilson (aged 8) and Eliza (aged 5) listed in the poor school children records in Richland, but no parents were associated with them.[9] In 1837, I find Mark (aged 9) and Eliza (aged 6) living 30 miles away in East Vincent, Chester County, Pennsylvania.[10] This time, their father was identified as William Wilson. With “William Wilson” being a common name and having no prior evidence of any Wilson from this or related lines living in East Vincent, I wanted to provide greater evidence.

In consulting the poor outdoor allowance records, I find several references for monies being given to a William and Sarah Wilson between 25 July 1837 and 28 September 1841 (note: William Wilson married Sarah Thompson 25 February 1819 in Doylestown, Bucks County[11]). Unfortunately, the Outdoor Allowance entry did not list the township where William and Sarah Wilson lived, but a Thomas Jacobs facilitated one of the payments in 1837, and Jacobs lived in East Vincent in 1840.[12]

What is also interesting to note is that the Eliza Wilson mentioned above is the same Eliza (Wilson) Hill mentioned in the previous blog post as being the sister identified in the 1896 deposition of Sarah (Wilson) McKinstry, who applied for her deceased husband’s Civil War pension.

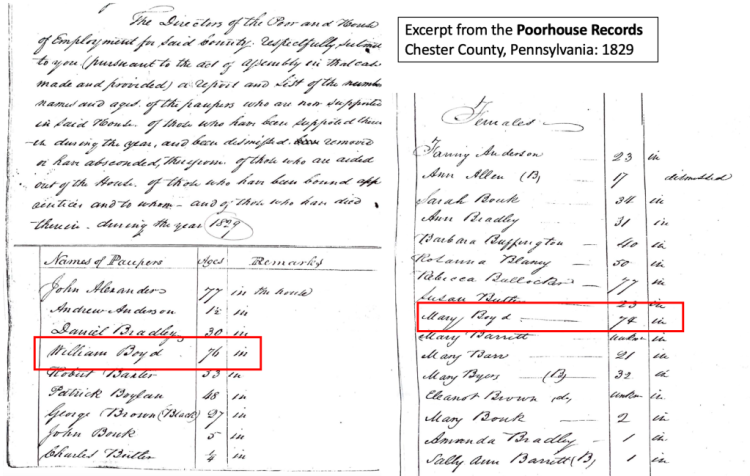

Poorhouse Admission Books

Poorhouse admission books often provide a simple listing of who entered, resided, or left the poorhouse for a given year. Entries can include their age.

William Boyd (1753-1836) and Mary (McMasters) Boyd (1755-1832)

My 5x great-grandfather, William Boyd, last appeared in census records in 1810, [13] and likely lived with children thereafter. I was able to pick up his whereabouts after 1810 in poorhouse records.

William and Mary (McMasters) Boyd entered the Poorhouse in East Bradford, Chester County from East Nottingham in 1829, likely from the residence of their daughter, Jane (Boyd) McDonald).[14] For the years between 1829 through 1832, William and Mary resided in the Poorhouse and records captured their age.[15]

Mary is recorded in the registers as dying in the Poorhouse in 1832.[16]

William Boyd is recorded as having left the Poorhouse in 1833 after the death of his wife. William Boyd’s will was dated 7 March 1835,[17] he died on 30 January 1836,[18] and his will was probated in 9 July 1839.[19]

Summary

Poorhouse records are outstanding sources for understanding the plight of our ancestors who struggled economically. These records may also help us understand how and why our ancestors ended up in the poorhouse. Some may be quick to judge those who ended up in the poorhouse, but statistical analysis of intake records from the 19th century indicates that about 90% were related to physical and mental illness, trauma, or debility.[20] Only about 10% of poorhouse admissions were associated with “moral failures”, such as intemperance, venereal disease, or pregnancy.

The availability of poorhouse records varies by state and county. If you know or suspect your ancestor was poor and may have received assistance, check with local genealogical or historical societies to see if records exist for your locale. In Chester County, Pennsylvania for example, poorhouse records are found with the county archives, which is a joint venture between county government and the county history center.[21] Chester County also has excellent indexes and a convenient, efficient, and affordable procedure for ordering copies of records. Some records are found free on FamilySearch.org but are not always indexed.

In the next post, which is the third and final posts in the “researching poor ancestors” series , learn about debtor records.

Don’t miss new blog posts. Complete the form below to be notified every time I write a new blog.

Sources

[1] Chester County, Pennsylvania, “Poor School Children Records, 1810-1842: General Information”, Chester County Archives, West Chester (www.chesco.org, accessed 24 April 2022).

[2] Pension Application, William Boyd, Sergeant, Revolutionary War, “Declaration of William Boyd in order to obtain the benefit of the Act of Congress passed June 7,1832”, dated 9 April 1833, Pension Application S.22,127, Pension Office, War Department, Washington, DC; online database with images, Fold3 (www.fold3.com, accessed 31 July 2018).

[3] 1800 U.S. census, Chester County, Pennsylvania, population schedule, East Nottingham, p. 866, image 1 of 3, William Boyd; database with image, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com, accessed 14 March 2022); Family History Library Film 363339, roll 36. And 1810 U.S. census, Chester County, Pennsylvania, population schedule, East Nottingham, p. 202, image 4 of 5, Wm Boyde [Boyd]; database with image, Ancestry(www.ancestry.com, accessed 14 March 2022); Family History Library Film 193673, roll 47.

[4] Chester County, Pennsylvania, Poor School Children Records, 1810-1842, Jane Boyd, Mary Boyd, Charlotte Boyd, children of William and Mary Boyd (1810), East Nottingham; Chester County Archives, West Chester.

[5] Chester County, Pennsylvania, will (book 17, p. 264), William Boyd (1835, Chester County), Recorder of Wills, Clerk of Orphans’ Court, West Chester.

[6] The Daily Republican (1884, July 22), “Capt. Ira R. Butler”, p. 4, col. 1, Monongahela, PA; online database, https://Newspapers.com, accessed 14 March 2022.

[7] Chester County, Pennsylvania, “Outdoor Allowances, 1800-1856”, Chester County Archives, West Chester (www.chesco.org, accessed 24 April 2022).

[8] 1830 U.S. census, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, population schedule, Richland, p. 221, image 11 of 20, William Wilson; database with image, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com, accessed 22 April 2021); NARA microfilm publication M19, roll146.

[9] Bucks County, Pennsylvania Tax Records, 1782-1860, Mark Wilson and Eliza Wilson (1836), Richland, image 30 of 31; database with image, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com, accessed 24 April 2021); citing Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Tax Records, 1782-1860, Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown.

[10] Chester County, Pennsylvania, Poor School Children Records, 1810-1842, Mark and Eliza Wilson (1837), East Vincent, p. 473 of 505; database with index, Chester County Archives (www.chesco.org, accessed 24 April 2021).

[11] Chester County, Pennsylvania, U.S., Directors of the Poor Outdoor Allowance Books, 1827-1843, William and Sarah Wilson (1837), Volume 2, p. 231-232. And Smith, C.A. and F.W. Waite (1986), Bucks County Intelligencer Marriage Notices, 1804-1860, Doylestown, PA: Bucks County Genealogical Society.

[12] 1840 U.S. census, Chester County, Pennsylvania, population schedule, East Vincent, p. 287, image 1 of 16, Thomas Jacobs; database with image, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com, accessed 21 May 2021); citing NARA microfilm M704, roll 453-454.

[13] 1810 U.S. census, Chester County, Pennsylvania, population schedule, East Nottingham, p. 202, image 4 of 5, Wm Boyde [Boyd]; database with image, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com, accessed 14 March 2022); Family History Library Film 193673, roll 47.

[14] Chester County, Poorhouse Admissions Alphabet Book 1826-1843, William and Mary Boyd (1829); database, Chester County Archives (www.chesco.org, accessed 24 April 2022), West Chester.

[15] Chester County Pennsylvania, Poorhouse Admissions 1800-1858, Mary Boyd (1829, 1830, 1831), Book RQS; database, Chester County Archives (www.chesco.org, accessed 24 April 2022), West Chester. And Chester County Pennsylvania, Poorhouse Admissions 1800-1858, William Boyd (1829, 1830, 1832), Book RQS; database, Chester County Archives (www.chesco.org, accessed 24 April 2022), West Chester.

[16] Chester County Pennsylvania, Poorhouse Admissions 1800-1858, Mary Boyd (1832), Book RQS; database, Chester County Archives (www.chesco.org, accessed 24 April 2022), West Chester.

[17] Chester County, Pennsylvania, will (book 17, p. 264), William Boyd (1835, Chester County), Recorder of Wills, Clerk of Orphans’ Court, West Chester.

[18] General Accounting Office, Final Payment Voucher, William Boyd (30 January 1836); database with image, Fold3 (www.Fold3.com, accessed 24 September 2018).

[19] Chester County, Pennsylvania, will (book 17, p. 264), William Boyd (1835, Chester County), Recorder of Wills, Clerk of Orphans’ Court, West Chester.

[20] Bourque, Monique (2003), “Populating the Poorhouse: A Reassessment of Poor Relief in the Antebellum Delaware Valley,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of the Mid-Atlantic Studies, 70(4), pp. 397-432.

[21] Chester County Archives, West Chester, Pennsylvania: https://www.chesco.org/192/Archives-Records.

One thought on “Poor Ancestors are not Invisible: Part 2, Poorhouse Records”